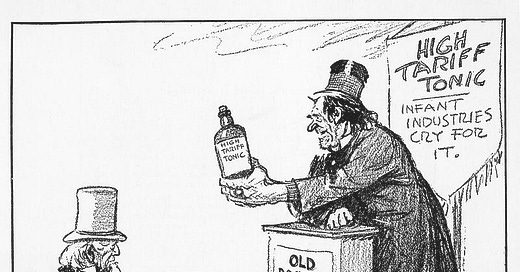

The beggar‑thy‑neighbor trade wars of the 1920s–30s represent a cautionary chapter in economic history, where countries sought to protect their domestic industries at the expense of international cooperation. At the heart of these policies was the belief that a nation’s prosperity could be secured by reducing imports and promoting local production. The most notorious example was the U.S. Smoot‑Hawley Tariff Act of 1930, which imposed steep tariffs on thousands of imported goods. Instead of revitalizing the American economy during the Great Depression, these measures sparked a cascade of retaliatory tariffs worldwide, leading to a contraction in global trade that exacerbated economic decline, which in turn was a factor leading to the second world war.

In this era, protectionism was seen as a direct method of economic survival. Governments believed that by raising barriers to imports, they could protect domestic jobs and industries from the ravages of an international downturn. However, the unintended consequence was a series of trade conflicts that deepened the global economic malaise. As countries engaged in tit‑for‑tat tariff escalations, international commerce shrank dramatically, foreign markets dried up, and economic recovery became even more elusive. The beggar‑thy‑neighbor strategy, while aiming to secure short‑term national gains, ended up undermining the collective economic stability of the interconnected global market.

Fast forward to today, and the world faces a new breed of trade wars, though the context and instruments have evolved. Modern trade conflicts, such as the notable tensions between the United States, Canada, Mexico and China, still involve the imposition of tariffs and trade barriers. However, today’s disputes are more complex and multifaceted. Instead of solely relying on traditional tariffs, modern nations employ a range of tools including sanctions, export controls, and restrictions on technology transfers. These measures not only target physical goods but also intangible assets like intellectual property and digital services, reflecting the transformation of the global economy into one that is deeply integrated with technology and information flows.

Despite the evolution of trade disputes, the core similarities with the 1920s–30s remain striking. Both eras exhibit a focus on national self‑interest and the willingness to sacrifice broader international cooperation in favor of short‑term economic gains. In both cases, the imposition of trade barriers tends to generate retaliatory measures, ultimately disrupting global supply chains and economic stability. However, today’s interconnected world—with its advanced communication networks, sophisticated financial systems, and interdependent supply chains—makes the consequences of such conflicts even more pronounced. While the economic interdependence of nations can be a source of strength, it also means that modern trade wars have the potential to ripple across industries and borders with unprecedented speed.

The beggar‑thy‑neighbor trade wars of the early 20th century and Trump's unprovoked trade conflicts share a fundamental tension between national protectionism and global economic interdependence. Both approaches, despite their differences in strategy and context, reveal the inherent risks of unilateral economic policies in an interconnected world. while protectionist measures may offer temporary relief for domestic industries, they can also ignite retaliatory actions that undermine global prosperity. Canada, Mexico and China’s immediate responses cause one to question whether the U.S. will glean any benefit, even in the short term. In the long term, an isolated, despised U.S. will have little chance of for stalling escalation.

Someone should tell Trump that sometimes trade wars have ended up on battlefields.